Inflation in the Twenty-First Century Part III: A Circular Flow No Longer

Foreign buyers of Treasury bonds are getting harder to find

When the Rise Of Carry was published my teenage son, a Covid-era stock speculator took a copy to his room. It sat unopened for months.

Then one day:

Son: “Dad, we need to talk.”

Teenager. Talking? Not good.

Me: “Sure, what’s up.”

Son: “Figure 2.3 is way too complicated, no one is going to get it.”

Me: “What?”

Son: “You know, your book. Figure 2.3. The Circular Flow Of Dollars. It’s too busy.”

Me: “You read the book?”

Son: “That’s what I’m trying to tell you. I did. Up until Figure 2.3!”

Figure 2.3 was our attempt to show how dollars circulated through the global economy. Dollars left the U.S. as payments for goods and services, or as part of carry trades, but a lot of them found their way back to the U.S. in the form of Treasury bond purchases. This ‘circular flow’ provided a source of price-insensitive funding for the US government deficit.

It’s a complex story, which we tried to simplify, but it was - clearly - not simple enough.

Below is another attempt at Figure 2.3 - slimmed down to focus just on dollars related to trade flows between the US and China. The persistent US current account deficit means dollars moved from the US to Chinese companies, who then sold them to the central bank in exchange for local currency. Those dollars then became part of China’s foreign exchange reserves and a large fraction of those reserves were invested in U.S. Treasuries1.

We worked on the book for years before its publication in December 2019 and, as we typed away, the flow was already changing. China began a gradual process of diversifying its FX reserves investment in 2007 and this process has accelerated since 2011.

The picture now looks more like the chart below. The deficit between the US and China still exists, but dollars no longer get stockpiled as reserves. Instead, China has built a sophisticated system for using that money to invest in a range of both foreign and domestic assets. My upcoming interview with Zoe Liu, author of Sovereign Funds: How The Communist Party of China Finances Its Global Ambitions, digs into the details. The key point for this post is that the once circular flow of dollars is no longer.

Why has China stopped buying Treasuries?

First, they own a lot. More than they need to manage the exchange rate, although this is being tested as we speak. Second, after the GFC, Treasuries became low-yielding assets and there was an uncomfortable opportunity cost to putting more money into something that barely kept up with inflation. Lastly, politics - the U.S. cutoff access to Russia’s central bank assets, couldn’t the same thing happen to China?

Other countries made similar calculations. The result has been a halt in Treasury purchases from China as well as major oil and commodity exporters. I’ve tried to capture this in the graph below. The orange bars show the total change in Treasury bond holdings and the grey bars the cumulative current account balance with the U.S.

From 2000-2010, these countries had a cumulative surplus with the US of $3.2 trillion and increased their holdings of Treasuries by $2 trillion. This is the circular flow we wrote about. Since then they’ve continued to accumulate dollars, but have stopped adding to their ownership of Treasuries.

Did the U.S. government react to this fall in demand for their bonds by selling fewer of them? Uh, no.

Did the Treasury bond market react to falling demand by pushing prices down and interest rates up? Until very recently, also no.

So what happened? Who replaced the demand?

First, there was an increase in Treasury buying from “financial centers” - places like the U.K., Switzerland, Cayman Islands, etc. Some of this activity - maybe a lot - was on behalf of those countries that stopped buying them directly. But the real whale was the Fed, which increased its holdings of Treasuries by $4.0 trillion from 2011-2022.

Here is where things stand now:

China & the Oil/Commodity countries seem unlikely to buy more Treasuries.

Indirect purchases through financial centers will continue, but I bet these taper off as countries worry about the US improving its ability to trace the bonds’ ultimate ownership.

The Fed is trying to reduce its Treasury holdings.

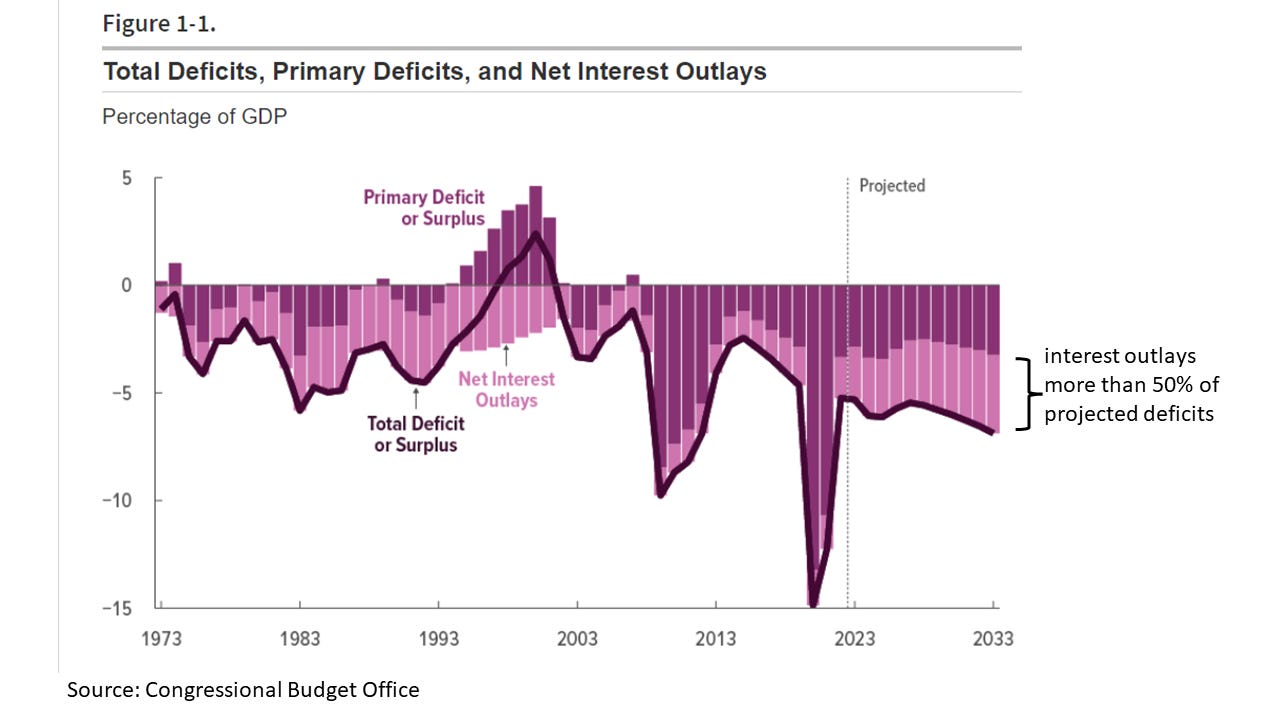

In other words, some huge buyers want to stay on the sidelines. Meanwhile, the huge seller - the US government - is going to sell even more because it is projected to run large deficits for…well forever really. And this projection, shown below, assumes long-term rates of only 4%.

Is 4% enough to attract other buyers?

If you believe inflation will be 2% then probably yes. If you believe inflation will be 3%, 4%, or more…then no, bond yields need to be higher. But with rates at, say, 6% the ugly deficit picture above gets uglier.

And that is where the story comes back to inflation.

At some point the Fed is going to get squeezed. It could get squeezed into allowing inflation to run higher because inflation is a stealth tax and what better way to finance a stubborn deficit than a stealth tax.

And it could get squeezed into keeping long-term rates low through buying bonds. Fed bond buying was not inflationary in the pre-Covid world, but purchases designed to finance a deficit would be.

Of course there are alternate scenarios.

For instance, productivity growth might accelerate, bringing both inflation and the deficit down. This is what Mark Mills, author of The Cloud Revolution, and my guest on this Ideas Lab podcast, expects.

I hope this happens! I just don’t know enough to judge the likelihood.

What I do know is that the flow of dollars around the world has changed and that makes the mechanics of financing the US deficit more challenging, which in turn increases the likelihood that inflation will be used as tool to manage it.

To keep the diagram simple, I’ve left out the arrow that completes the circle. The US government deficit, partly financed by Treasury purchases from abroad, puts money into the pockets of the US private sector, which then buys goods and services from China and the loop continues.

You Might Also Like

Inflation in the Twenty-First Century Part I: The Battle Ain't Over Yet

Inflation in the Twenty-First Century Part II: Unintended Consequences

CC bringing the heat per usual ... it only took you 3 years to update the graph ... “thanks, Dad.”

Thank you for writing this letter, from a Haas alumni! From what you have described, this may be another reason we will have an inverted yield curve for longer, but that does not necessarily mean a recession is imminent!