Inflation in the Twenty-First Century Part II: Unintended Consequences

The Carry Regime's legacy adds new challenges and costs to the inflation fight

My house in California sits within a short walk of the Hayward fault. Most of the time nothing happens, but occasionally we are jolted awake by an earthquake.

The US inflation experience in the decades prior to Covid was similar. A deflationary tectonic plate driven by demographics and globalization pushed wages and traded goods prices lower. Grinding against this was an inflationary plate propelled by liquidity from private carry traders, who dramatically expanded their reach as interest rates fell from double digits to zero.

Most of the time these forces offset each other and inflation was ‘normal’. But occasionally - 1998, 2007-8, 2011, 2020 - the liquidity flow driving the inflationary plate disappeared and we suddenly experienced a deflationary earthquake. To prevent outright deflation central banks stepped in, providing enough of their own liquidity to restore this fragile balance.

Last week I wrote about how the forces driving the deflationary plate are reversing, creating the prospect of higher long-term inflation despite its recent decline. Central banks have countered by raising interesting rates, attempting to flip the direction of the monetary plate.

But it’s not as simple as just changing direction. Fighting deflation over the last four decades has changed the financial landscape, creating unintended challenges for central banks as they now fight inflation.

Fighting Inflation in a Levered World

Carry trades always increase liquidity and leverage. As private carry trades expanded, markets became more liquid and balance sheets more levered than the last time we fought inflation in the 1970’s and 80’s. The graph below captures the broad trend in debt across G7 countries. This is an underestimate because it does not capture off-balance sheet leverage, for example from derivative positions, that are likely very large.

The point isn’t that increased leverage is ‘bad’. But higher leverage does increase fragility. Michael Howell, author of Capital Wars, says that modern markets are about refinancing. Most debt isn’t repaid when it comes due, it’s rolled over. Rolling over at 7% is a lot more costly than rolling over at 4%. For some that extra cost is the difference between being viable and being, well, not viable.

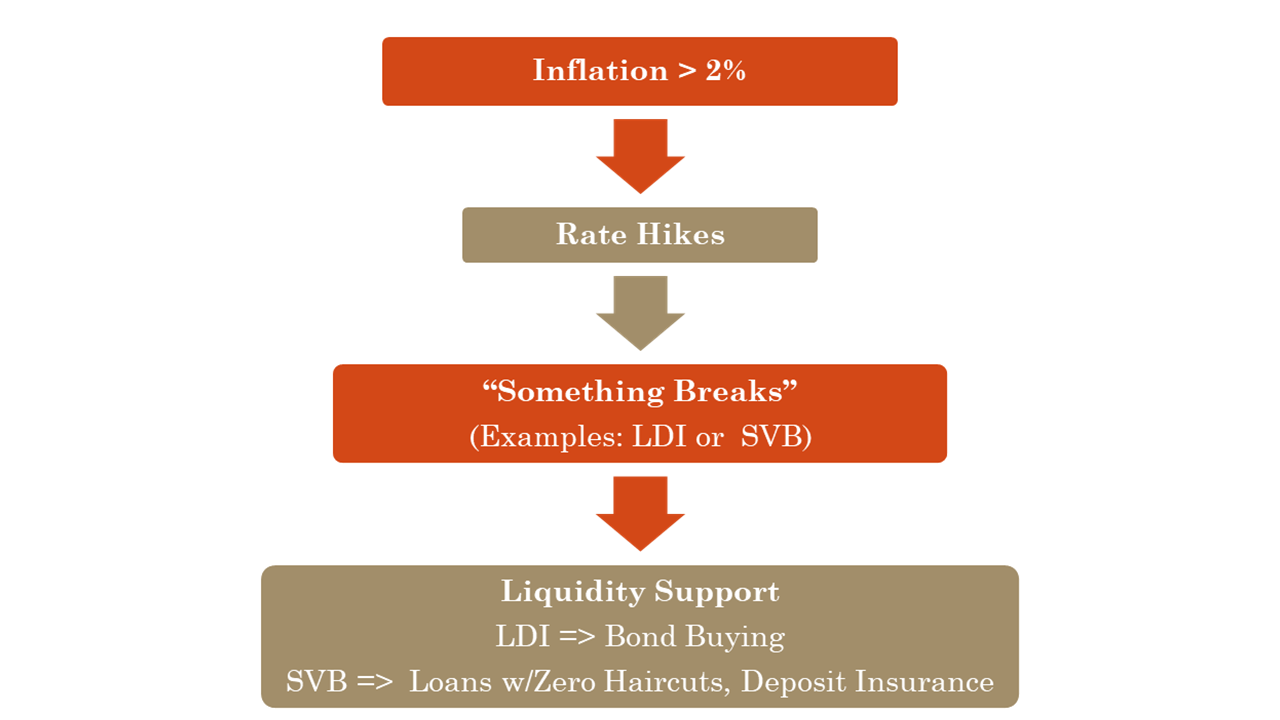

I’ve tried to capture this dynamic in the graph below:

In a levered world, raising interest rates to fight inflation risks triggering a financial crisis. (And, perhaps equally frightening, introducing us to a new acronym.) We’ve seen two of these in the past year. The first was the liability driven investment (LDI) crisis among British pension funds and later came the US regional banking panic triggered by Silicon Valley Bank’s (SVB) failure.

When a pocket of the market breaks the rationale for support is that those involved are “solvent, but illiquid”. If the market believes this, then the central bank’s liquidity support stems the crisis, volatility falls and, after a reflective pause, rates can be raised again to fight inflation. Eventually, inflation falls back to target. This is the ‘soft landing’ path outlined below in red.

Unfortunately it’s perfectly plausible that something else will break before the soft landing is achieved. In that case we are on the grey bit of the diagram, heading back to more liquidity support and again waiting for the market to agree or disagree with the "solvent, but illiquid” explanation.

The scenario we warned about in The Rise Of Carry was the one on the right where markets disagrees. In that world liquidity support does not calm markets and more support is necessary. But doubling down on liquidity when inflation is above target is dangerous, it risks a severe breakdown in market confidence. This is exactly what we meant in 2019 when we wrote:

“…the carry regime creates the sense that central banks are all powerful even as, in a fundamental sense, they are becoming weak.”

Central banks themselves recognize the issue. Here is a quote from Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey following his liquidity support for British pension funds last year:

“There may appear to be a tension here between tightening monetary policy as we must, including so-called Quantitative Tightening, and buying government debt to ease a critical threat to financial stability.”

To its great credit the Bank of England wrote an excellent post-mortem of the LDI crisis where they cover all these various contradictions in detail - including flow charts that rival those you see here.

In sum, the rise in debt that has characterized the Carry Regime makes financial markets more fragile and more likely to ‘break’ when interest rates are raised. The response to something breaking increases the risk of inflation by adding more liquidity. In the worst case scenario, if this cycle happens enough, the Fed could lose the market’s confidence.

Not saying it’s gonna happen…but it’s a logical possibility.

Staying The Course Is Costly

Even if this does not happen, even if central bank credibility remains intact, an important second order risk is the negative impact on public finances.

When central banks engage in liquidity support they acquire long-term assets like government bonds which pay a fixed rate of interest. These assets are financed by new short-term liabilities. In the pre-Covid deflationary era this was a classic carry trade because the interest rates on the bonds acquired were higher than the virtually zero interest rates on the liabilities created to fund their purchase.

Now the math is different.

As interest rates have risen to fight inflation the cost of the Fed’s liabilities have also gone up. The graph below shows just how quickly this happened. In 2021, the Fed held an $8.8 trillion portfolio that earned interest of $117 billion. What did it cost to finance that portfolio? Almost zero! But in 2023 my guesstimate is that the Fed’s interest expense will be about $270 billion vs. $160 billion of interest income1.

Last year the Fed sent about $60 billion in profits to the Treasury. This year net interest income could be negative $90 billion. Fighting inflation with a balance sheet swollen from liquidity support could lead to a $150 billion deterioration in public finances between 2022 and 2023. The US federal deficit is about $2 trillion, so that $150 billion swing is about 7.5% of the deficit.

The Fed is determined to stay the course, to keep rates high until an inflation rate of 2% is reestablished as the norm. I’m not saying this is wrong, but it will be costly.

This extra cost comes at a time when previously reliable sources of financing are falling away. For much of the past two decades foreign governments and sovereign wealth funds have helped the US finance its deficit by being relatively price insensitive buyers of US Treasury debt. In a coming post I’ll explain how this worked and how its changing.

A key driver of this change is the behavior of China. We’ll peak under the hood of their global financing activities on the next Ideas Lab podcast when I talk with Zoe Liu author of the new book: Sovereign Funds: How the Communist Party of China Finances Its Global Ambitions.

Stay tuned.

The interest expense number is arrived at by using the Fed’s H.1.4 statements to get the weekly total of interest paying liabilities from which I calculate a weekly interest cost through August 10th. From there I assume interest rates stay the same for the rest of 2023 and liabilities decline along with the Fed’s bond portfolio. I compared this estimation method vs. the audited annual interest expense for 2018-2022. My estimates get close to the actual expenses realized in those years. As long as there are no big balance sheet changes this year, my interest expense number ought to be a reasonable forecast.

There is more margin for error on the estimate for interest income. In 2022 the Fed earned a 2% yield on its portfolio of interest bearing assets. I assume they will earn this same yield in 2023 and apply this to the Fed’s average weekly interest paying assets to calculate interest earned through August 10th. I then assume assets levels decline over the rest of the year as the Fed reduces its holdings of bonds and scales back its support for regional banks. I assume bond holdings are reduced at the same pace we have seen year-to-date and that bank support falls at the same pace experienced since its peak in the spring. Other than balance sheet size, the big unknown is the yield on its assets. Asset yields were 2.8%, 2.5%, 1.4% & 1.4% in 2018-2021, so 2% seems a defendable estimate.

"including flow charts that rival those you see here" is the content I subscribe for!