The Measure of Progress

The next generation of economic statistics begins to emerge

“The more research I’ve done on economic statistics, the less certain I am that we know anything solid about today’s economy.”

Diane Coyle’s quote is worrying. The Cambridge professor has spent her professional life studying economic statistics, even publishing a book in 2014 called “GDP: A Brief But Affectionate History”. Her latest book: The Measure of Progress, explains how our current system of statistics renders large swathes of the economy invisible, why that matters and what a new framework might look like.

GDP: A Good But Ageing Idea

The idea of GDP crystallized during and immediately after World War II as a way to measure the economy’s capacity to produce. Producing at that time mostly meant manufacturing and agriculture. Of course, we still manufacture things, but the process has changed, making it trickier to accurately assign the economic value added along the way. Some production has evolved to a design and outsourcing model. For example, almost all the world’s most advanced semiconductors are made by just one company, Taiwan’s TSMC, but designed by other firms. That shift has meant less chip manufacturing in the US, but also the creation of new firms like Nvidia whose focus on design has led to enormous value creation.

Coyle also talks about “servitized” manufacturers, like Rolls-Royce, a company that makes sophisticated turbines, but earns two-thirds of its profits on after-sale service. Is it a service company or a manufacturer? What about Apple? It designs iPhones in California, but famously uses companies from all over the world to construct them. As Coyle says:

If you want to compare manufacturing sectors across countries, you would really need to go into the detail to understand, well, where did they put this company? Which sector did they put it in?

It’s become really difficult to get a handle on what actually is the production capacity of a national economy? Where are the profits and wages being generated from, and what actually is happening to the trade balance?

Concern about the production capacity of the US was a fundamental driver of both the Biden and Trump administrations. For something so important we should aim to understand it better.

Coyle’s book contains a LOT more examples of GDP struggling to capture the modern economy. Here are a few:

“Free” Goods. Tools like Gmail, open-source software, and user innovation provide real value but are invisible in GDP.

Disintermediation. The relentless effort of companies to push work on to their clients. Think self-checkout, online banking, and customer service chatbots. These improve measured productivity and profits, because companies employ fewer workers. But some of that work is still being done (by us!), it’s just not counted. And the replacement is often sub-par, as with service chatbots, or bad for mental health, as when some poor soul is stuck behind me at a self-checkout line. This “time tax” is real, but invisible in economic statistics.

Technology & Ideas. Innovations often reduce spending (and GDP) while improving wellbeing. For example, the approved drug for treating macular degeneration in the US costs $2,000 per dose. But a cancer medicine, Avastin, turns out to be just as effective and costs $55. Switching would reduce spending (GDP) but increase health outcomes.

GDP Isn’t Real

GDP can be calculated by adding up the value of what people spend, what they earn or what gets produced. In principle those things should be the same. But comparing those values through time is complicated by inflation. Nominal GDP might grow simply because prices went up. “Real” GDP adjusts for this by deflating those values using a measure of inflation. But Coyle says, as soon as you do this, the three methods don’t add up:

Once you apply the right price index to each (GDP) component, then the things that you get out are not going to add up at all. In fact, very often it’s not even obvious what kind of number you’ve created by using a price index to turn into this concept of real value.

Real GDP growth has been a foundational measure of the economy’s performance, so this inflation problem matters. The problem isn’t new, but is now compounded by the fact that the starting point, nominal GDP, is itself a failing to capture a lot of economic value:

If you really want to understand how people’s lives are going, is this the right way to go about it with this obscure technical set of GDP index numbers that nobody really understands?

Six Capitals

Coyle advocates for a new, comprehensive measure of wealth based on six types of capital: (1) physical (2) natural (3) human (4) knowledge (5) institutional (6) social. She wants to see national balance sheets that measure the stocks of each, along with a process that tracks the flows of services these capitals generate.

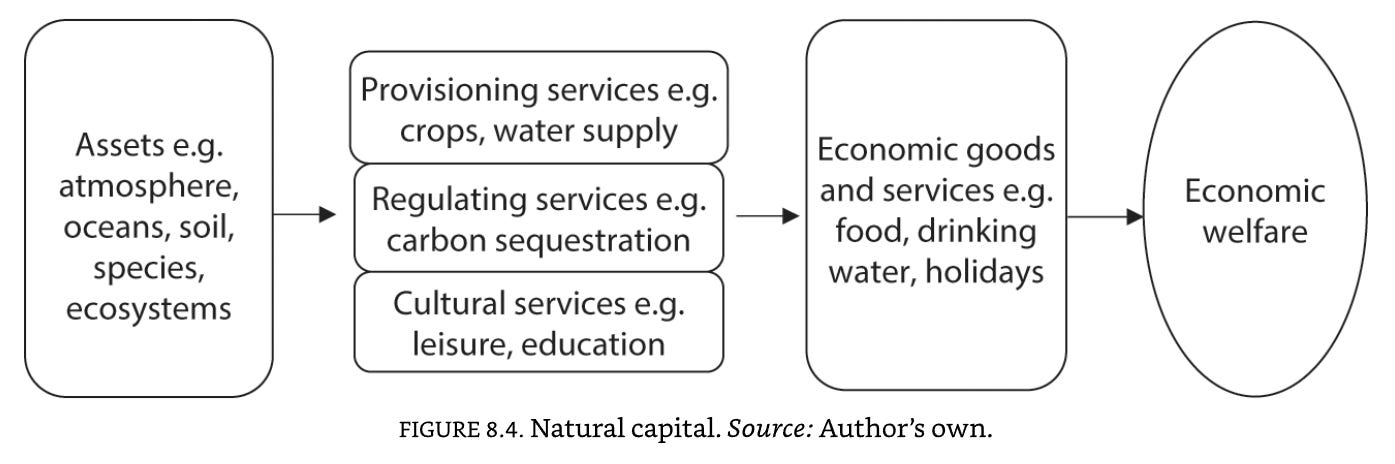

The diagram below from her book illustrates the idea with natural capital. We start with a stock of natural assets on the left, which generate a range of services that might in term impact other capitals. Clear air and water may increase the stock of social capital by promoting leisure and athletics. Soil quality can impact agricultural productivity, etc.

To those of us habituated to dealing with ‘hard data’, creating a balance sheet of things like natural, institutional or social capital might seem too vague. But there are plenty of examples where economic growth is clearly relying on these assets. Think about Singapore: after World War II it had few physical assets and little manufacturing, yet grew to generate one of the highest per-capital incomes in the world. Clearly it was relying on other, unmeasured assets, to achieve this. Probably some mix of human, knowledge and social capital. Without an accounting framework we are left to guess. My wife’s home country of New Zealand is another example. Tourism generates 5-7% of its GDP. This activity relies directly on maintaining a pristine stock of natural capital.

An oft-cited, but invalid, criticism is that some of the six capitals have no market prices. Without market prices how can we generate a balance sheet measure of value? That is a significant challenge. But remember, market prices used for things like physical capital don’t map to economic value unless there is perfect competition. We know many modern, information-oriented markets do not meet this criteria from the behavior of the tech giants that dominate them. Their aim is to achieve scale first and then use a dominant position to earn supernormal profits, with a corresponding collapse in product quality1.

Another issue with market prices is their failure to embed externalities, the most obvious example being the omission of environmental costs from fossil fuel assets. The market values of those assets are overstated because there is no corresponding entry that accounts for their full usage costs. And if you are a Florida property owner who can’t insure your coastal home because of rising sea levels, you’ll appreciate how real these costs are.

But this “full costing” idea applies to renewables as well - there is environmental degradation from extracting the materials needed to produce batteries, etc. That’s why Coyle’s framework make sense. In her world, fossil fuel use would “debit” natural capital but also “credit” the other capitals it helps create. Renewable power for the same use might involve a more complex set of entries on the natural capital balance sheet, depleting some, increasing others. It would force a thoughtful and more transparent analysis. The broader point is that market prices aren’t perfect and therefore lack of market prices is not a valid reason to abandon valuation of things like natural or institutional capital.

Coyle admits all this presents enormous measurement challenges and the journey is just beginning. I started the Idea Lab newsletter and podcast to highlight ideas that will define our economic future. This is one of them. If you want to dig into the detail, Coyle’s book will lead you to the right research. If you want to understand why this is so important, click below and listen to our conversation.

Spotify:

Apple Podcasts:

Compare the quality of Google searches now to 10 years ago. Or the user-experience of Instagram before and after being gobbled up by Facebook. This is my rant, not Coyle’s, but I’m hardly alone in noticing the poor quality of big Tech products. For more see Enshittificaiton.

You Might Also Like:

How Economics Can Help Navigate Life’s Trickiest Questions

Yes! Thanks for contributing to economic growth! And note that the subscription price has not been adjusted for inflation, so in real terms it keep getting cheaper to support my work.

very thoughtful, thx