Shocks, Crises and False Alarms

How to think through doom mongering predictions for the economy.

How should you respond to predictions of economic doom?

It’s a question I’ve wrestled with a lot since the 2008 market meltdown, when I was overseeing a leveraged hedge fund. Watching the banks where you’ve deposited several hundred million dollars of client money teeter on the edge of bankruptcy for 18 months ain’t fun. I spent the next decade following forecasts that assigned too high a likelihood to another crash. Acting on these views bought a bit of extra sleep, but at the expense of being too conservative in my investments.

This is why I was intrigued to read Philipp Carlsson’s new book Shocks, Crises and False Alarms: How To Assess True Macroeconomic Risk. I figured - he’s BCG’s chief economist, spends his days advising CEOs on how to interpret the economy, maybe he can help me as well.

If you are confronted with a doomsaying forecast, Carlsson’s advice is to demand an internally consistent and plausible path with signposts along the way that explain why disaster will happen. In other words, what specific actions does it require of both private and public sectors? What are the underlying economic drivers of those actions? How high is the bar for them to behave this way?

Throughout the book he applies this framework to evaluate a variety of doom-like predictions including runaway inflation, a debt crisis and mass unemployment from AI. He takes these possibilities seriously but concludes they are unlikely. In his own words: it’s rational to consider risk from the edges of the risk distribution. It is not rational to to assume those risks are at its center.

Since the ‘AI will put all of us out of work’ narrative feels the scariest, let's walk through his analysis, both to calm fears and illustrate his framework.

A New Era Of Tightness

The background to Carlsson’s analysis of the future is what he calls ‘a new era of tightness’, defined by labor scarcity and low unemployment. This era started around 2017 and he expects it to last a long time. Tight labor markets mean rising wages, a trend clearly evident in the data.

This is important because rising wages will eventually force firms adopt technology to replace workers and reduce costs. ‘Force’ is the key word here because Carlsson believes that the mere existence of cost-saving technology is rarely enough for companies to embrace it. Adoption needs to be thrust upon them by rising costs. A tight labor market, with rising wages and scarce workers is exactly the environment where this happens.

When this substitution of machines for labor takes place at-scale it drives down prices and leads to increasing output - the definition of productivity growth. That’s good for the economy as a whole, but isn’t it also the ‘AI puts us all out of work’ doomsday scenario we’re worried about?

No.

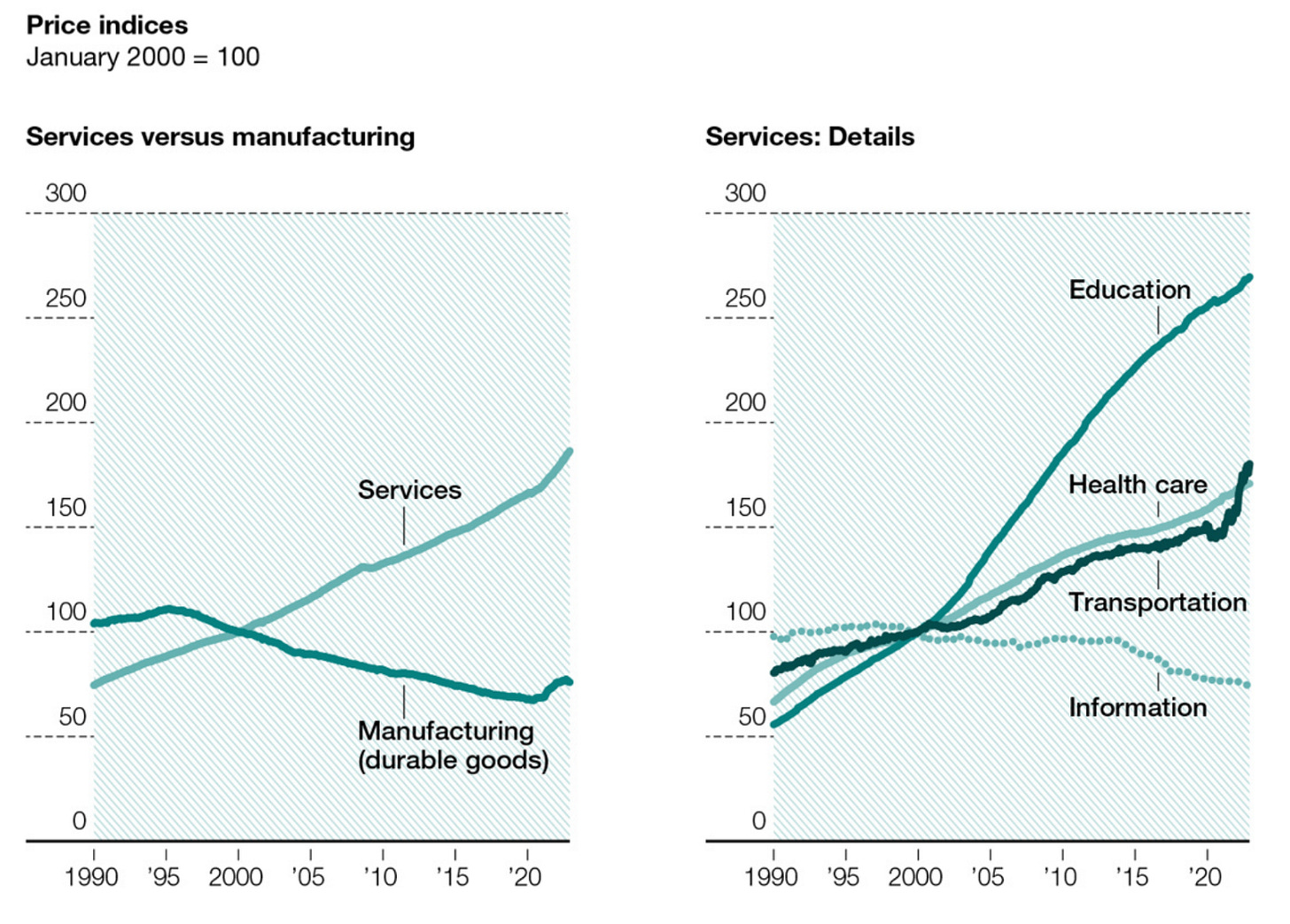

To understand why, start by looking at the graph below from Carlsson’s book. It tracks inflation in services vs. goods. On the left we see that services have gotten relentlessly more expensive and on the right we see the familiar culprits - education, health care and transport.

If technology replaces workers with machines in these sectors, that will cause job losses, at least temporarily. But it also means that the inflation-adjusted cost of these services will fall, boosting all of our real incomes. Imagine if future education and health care prices fell like the manufacturing prices on the left graph. I dare you to say that’s not exciting. Ok, any future fall is unlikely to be so dramatic, but even a modest decrease in the real cost for these services would be a huge deal, since we all use them.

This brings us to Carlsson’s key point - faster productivity growth means rising real incomes. And what will any red-blooded American do with more money? Spend it! That spending creates jobs - in new areas. This has been the story of the US economy over the last 150 years, a period that includes multiple waves of disruptive technology and an increase of nearly 150 million jobs.

Moving the punch bowl closer…then easing it away again

Carlsson’s framework helps dispel the doom about AI-driven mass unemployment. However, he’s also realistic about the size of the growth-enhancing productivity boost we can expect from new technology. Some forecasters predict a bump of 1% or 1.5%. His thinks that’s too high.

Remember, in his framework technology improves growth when it reduces labor costs at-scale and raises incomes. The sectors that really matter - education, health care, transport - are not easily amenable to this. That’s why Carlsson is cautious. He thinks a boost of 0.5% per year is more realistic. In terms of timing, his believes the impact will emerge in terms of years, not quarters.

This post focuses on only a small section of the book. Other important views that emerge:

Governments will be constrained in their ability to tactically stimulate the economy, but will retain the firepower they need to fight existential crises.

Tightness will give inflation an upward-bias, but it won’t become unanchored, like in the 1970’s.

Arguments that we are headed for a debt crisis are too focused on the levels of debt. Crises have emerged at far lower levels in the past and failed to emerge at far higher levels. The focus instead should be on expected economic growth rates compared to interest rates. On that measure the risk of a debt crises slides from the center of the distribution to the left. Still there, but not a risk he feels we should base behavior around.

I questioned him about all of these conclusions during our conversation on The Ideas Lab Podcast. Listen for yourself and then get his book to keep handy for the next time you bump into a doom monger.

Spotify:

Apple Podcasts: